Chicago has never recovered from the Meatpackers Strike of 1904. Though engulfed by flames in 1871, Chicago rose from its roots again like an oak forest on steroids. The Pullman Strike, put down by George Custer's replacements, Illinois Yellow-legs and Pinkerton's goons, was as nothing compared to what lay ahead on the tracks.

Chicago's steel tentacles pulled cattle, hogs, sheep and any other hoofed hide that could be tanned, eaten, rendered or husbanded to a vast yard owned by sharp men of business. The amalgamation of tanners, packers, renderers, and shippers had cheap, disorganized and willing pool of people to labor, bleed, and exploit - Czech, Irish, Lithuanian, Polish, Russian, Westphalian, Belgian, Prussian, Bavarian, Norwegian, and Swedish.

Some of those immigrants had skills as carpenters, millwrights, metal workers, coopers, cartwrights, and teamsters; most had no skills other than brute strength. Today they would be called Caucasian, though very few had passed through Caucasus to get to America.

On July 12, 1904, a strike was called by the Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butcher Workmen (AMC) whose President Michael Donnelly announced the strike.

The causes of the strike ranged from low wages to the excessive pace required while on the job. The strike lasted for nearly two months and included rioting and murder with few periods of peace. The strikers used tactics such as demonstrations and parades while the packers responded by hiring strikebreakers. Although factory conditions were unchanged, the strike had many far reaching effects on the city of Chicago, the union, and the nation as a whole. . . . The Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butcher Workmen played a major role in the strike. It was a giant organization and employed both skilled and unskilled workers, a circumstance often resented by skilled workers.(Halpern 32) Though unity was not one of the union's strong points, the union did give workers some sense of it, which was vital when the strike finally began. The main protagonists of the strike were the common laborers, the skilled and unskilled butchers of the Chicago packing plants. The workers, now somewhat organized, demanded higher pay and an end to the relentless "speeding up" of the packing progress. The typical laborer at the time of the strike was foreign, unskilled, worked long, hard hours, and was paid less than twenty cents an hour. The strikers were also very violent which resulted in numerous murders and riots. ("Strikers Firm" 2) ( Italics indicate secondary source used)

meatpackers_strike.htm

The murders and riots were in reaction to the bringing of strikebreakers, most African Americans from the South and hired goons to agitate and incite violence. Chicago Tribune archived articles from the period of the strike - roughly July through September 1904 bear witness to the actions and motives behind those acts.

The violence brought home to the heart of readers the intense frustration felt by the strikers and their families and the malice and greed that Chicago's leading families were willing to orchestrate in the name of profit. 8,750 strikebreakers, mostly miserably poor blacks, were lured with promises of a better life in Chicago and train fare to this Killing floor of the human heart. Strikers and their families were in fact starving despite the effort of Strike relief committees and the sympathy for strikers crossed state lines. However, the need to feed the greed was greater than articulating an agreement with the AMC. The owners intended to break this strike and they succeeded.

After a unanimous vote to maintain the strike, AMC President Michael Donnelly announced the strike ended on Sept. 9 1905 - 59 days after the strike was called.

The resulting antipathy between multi-cultural,lingual, and religious Caucasians and the strikebreaking African Americans would play out for next one hundred and two years in Chicago. The nature of race relations would always be reduced to the simple 'color of a man's skin' equation by people with the luxury of not being close to the conflict.

The descendants of the strikers would recoil from relations with the people who came North in the hope of a better life. They were shoved into combat with people themselves the victims of exploitation and those who profited by that combat. Those same descendants, one hundred and two years later, continue to be at odds with one another. The strikers descendants moved away as the Black Belt expanded to Berwyn, Cicero, Maywood and the southwest sides - places that since the 1904 strike have been branded as single-mindedly racist, unlike neighborhoods far removed from killing floors on the south side. The Armours and the Swifts and their co-industrialists did well by the strike and became clean with wealth, while the strikers and the strikebreakers were set at odds with one another and continue to be.

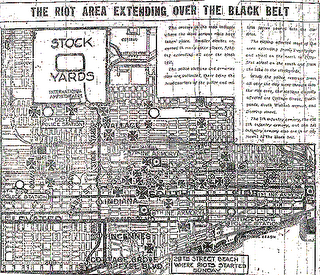

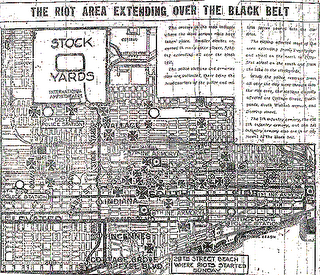

The horrific race riots of 1919 were confined to battlefields of Back of the Yards and the Black Belt. The fight for fair housing from the 1940's through the new millennium mirror that combat zone. Dr. King marched in Marquette Park, where the descendants of the strikers lived and not in Highland Park where the people who prospered by that broken strike might have taken root. Southside white ethnic neighborhoods continue to be referred to as 'racial hotbeds,' as recently as last week, in the Chicago media. Blacks continue to be pitted against ethnic whites and both exploited for political and economic gain.

Maybe, some talk about the causes and consequences of the 1904 Meatpackers Strike should preclude any 'Let's talk Race' challenge.

Sources

Halpern, Rick. Down on the Killing Floor: Black and White Workers in Chicago's Packinghouses, 1904 - 54. Urbana, Illinois : University of Illinois Press, 1997.

Strike is Ended; Men Surrender." Chicago Daily Tribune. 9 Sept. 1904

Read more...

Crossposted on

Crossposted on